Carlos Betancourt was just a kid who liked art class, recently transplanted from his native Puerto Rico, when he raised his hand at Miami Coral Park Senior High to be part of the army of volunteers that would help pull off a monumental-scale art project by a famous artist he had never heard of.

The year was 1983, and the artist was Christo. His Surrounded Islands turned Biscayne Bay into a string of giant hot-pink lily pads and put the town in the international spotlight. Betancourt helped stretch out part of the 6.5 million square feet of floating polypropylene fabric that encircled 11 tiny islands. It was mesmerizing, so much luminous pink spreading over teal waters.

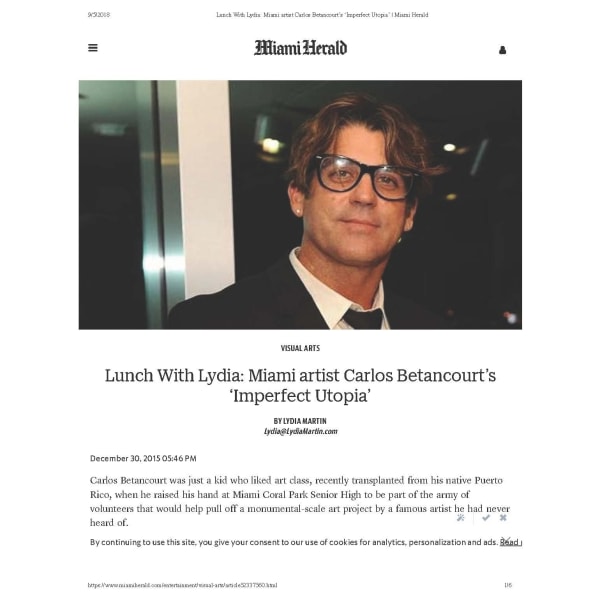

"I kind of became a groupie. I followed Christo around," says Betancourt, today an internationally collected artist. In October, Skira Rizzoli published a lush coffee table book of his oeuvre, Carlos Betancourt: Imperfect Utopia. In November, San Juan's Museo de Arte Contemporaneo opened a mid-career retrospective of his work, titled "Carlos Betancourt: Recollections." During December's Art Basel Miami Beach, he was feted at Miami Beach's SoHo House and was one of the artists showcased in "100+ Degrees in the Shade," a carefully curated survey of more than 150 local artists.

Christo didn't just introduce Betancourt to the world of major art. He introduced him to a seedy South Beach, which no one then guessed was on the verge of an artist-fueled renaissance. Betancourt would wind up playing a central role.

"We found out Christo was staying at the Leslie Hotel on Ocean Drive. So we went to check out the area. Nobody was really there, except all of the old people who sat in front of the hotels. But they were part of the charm," Betancourt says over lunch in the art-filled 1930s bungalow in El Portal that he shares with his partner and artistic collaborator, Alberto Latorre.

Soon after high school, Betancourt, who graduated from the Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale, joined the Miami Design Preservation League, which was working to save those faded Art Deco hotels. A little later, he opened a studio off Lincoln Road in which he lived, painted and made furniture designs. He called it Imperfect Utopia. In the early 1990s, it moved it to a bigger, more prominent space at 704 Lincoln Rd.

"My rent was about $280 a month. At the other, I didn't have a place to shower. There was an artist next door, Ali, who let me use his. When I moved to the Lincoln Road space, I had a sink that I could attach a hose to, and I would shower in the alley. My parents were horrified," says Betancourt, 49, who has pieces now in the collections of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and several other museums.

South Beach was emerging as a Bohemian paradise in the late 1980s as the fight to save the Art Deco district intensified, more and more artists opened studios in dilapidated spaces, an edgy gay scene developed and a decadent party circuit caught fire.

An authentic, underground cultural movement was being born, and often, Imperfect Utopia felt like ground zero. Artists and others who helped spark the renaissance congregated there for happenings. On any given day, you could run into Celia Cruz, Sandra Bernhard, Octavio Paz, Gianni Versace, Bruce Weber, Julian Schnabel.

Someone who popped in all the time was famed architect Morris Lapidus, king of MiMo. He designed the Fontainebleau, the Eden Roc, the 1950s reinvention of Lincoln Road as a pedestrian mall, but at that juncture was he nearly forgotten.

Betancourt happened to be one of his biggest fans.

"South Beach may be the last place that was able to develop organically, without the Internet or any of that forcing its gentrification," he says. "We were working to invent the future, surrounded by all of that architecture of optimism that Morris Lapidus and others built. There was such a collage of characters on the Beach then. Artists, drag queens, celebrities, aging burlesque dancers and switchboard operators, Holocaust survivors with numbers tattooed on their arms - and it was a very democratic scene."

Betancourt's work (interventions in nature, large-scale photography, painting, sculpture and more) often focuses on collaging and layering, referencing not only that high-octane mix that revived South Beach but also his own sense of identity. He's a Puerto Rican kid born to exiled Cuban parents who is as American as he is a son of the Caribbean.

"From the start, I was trying to make sense of all of these different pieces that made up who I was. I was trying to figure out how it all fit together and arrange it in a way that was comforting," he says. "My work still involves collecting objects, collecting history, collecting memory. Layering all of that, finding juxtapositions."

Much of his work bursts with beauty and color, and sometimes a touch of the Lapidus glitz. The visual optimism that drew Betancourt to South Beach especially shines through in his kaleidoscopic arrangements of everything from kitschy mementos to shards of dishes and pottery to flora collected from here and there.

One piece that speaks directly to the magical moment of South Beach's rebirth is 2008's The (Last) Supper, which appears in the artist's new book as a luxe foldout.

Posing amid a vibrantly hued, eye-popping assemblage of objects, totems and memorabilia are a collection of Betancourt's own friends, relatives, the characters he met back in the day.

"That time was about such defined, unique personalities and the democracy of mixing together and sharing all the infinite possibilities in front of us," he says. "There was an energy to that, a flamboyance. And that moment led to a lot of growth for the city. It led to Art Basel choosing to have their fair here instead of anywhere else in the world."

Betancourt is among a relatively small group local artists who have had a presence at Art Basel proper. His work has appeared on the convention center floor three or four times and has sold well, he says. For several years, his studio has been on Art Basel's official list of local artist studios to visit, which has brought collectors from around the world to his doorstep.

"I'm very fortunate. As my dealer says, you want to expose your work to as many audiences as possible," says Betancourt, who with Latorre, an architect, is working on designing and building a new studio in the Little Haiti area.